Discover our e-shop and access a digital catalogue of over 40.000 design products.

Go to shop9 April 2025

In this interview, Tom Dixon speaks with remarkable clarity and generosity about his relationship with materials, the role of improvisation and reinvention, the influence of music, and his view of the Salone del Mobile as a vibrant stage for contemporary design.

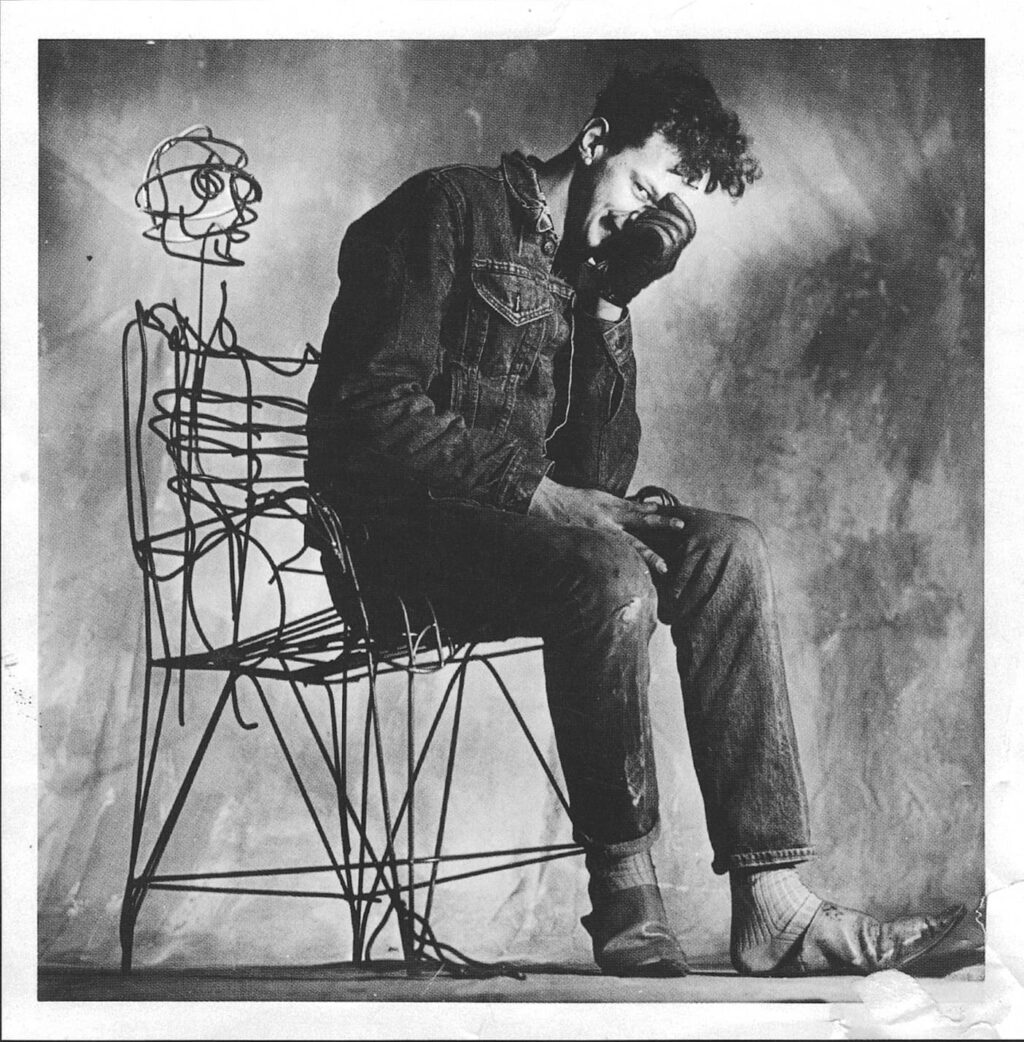

Unmistakable, eclectic, and radical, Tom Dixon stands as one of the most emblematic figures in today’s design landscape. A self-taught talent and tireless experimenter, he has turned raw materials into expressive language and the act of design into a form of storytelling. From the iconic S-Chair—born in London’s underground scene and now part of major museum collections—to his latest creations in furniture, lighting, and decorative objects, his creative world continues to expand in unexpected and ingenious directions.

Through passions, obsessions, and unconventional collaborations, a portrait emerges: that of a designer who has made intellectual independence and experimentation the driving forces of his work. A conversation rich in insight, offering a glimpse into the future of design while remaining rooted in its most authentic essence.

Q: Starting from your early inspiration, your career in design has been anything but conventional—from your early days experimenting with industrial materials to leading an internationally recognized design studio. How did your design journey begin?

A: Oh, wow—that’s a long story. It’s not easy to describe, because it was more of an evolution, a transformation, and a series of decisions along the way. I started out making things mostly for fun, and then people began buying them. In that sense, it was quite simple.

What really set it in motion was learning how to weld—not because I wanted to be a designer or get into manufacturing, but because I needed to repair my vintage cars and motorcycles. But as soon as I picked it up, I discovered that welding was an incredibly fast and powerful way to make things. It allowed me to create strong, tangible objects quickly, and I became completely fascinated by the technique.

While I was practicing, I naturally started making functional objects—chairs, lamps—and people took an interest in them. So there was this almost invisible transition: I moved from working in the music and nightclub business, which was how I made a living at the time, into making and selling objects.

Q: Was there any material you particularly fell in love with at the beginning, and how did your relationship with materials evolve over time?

A: Well, probably even before all that, when I was at school, the only department I really enjoyed being in was the ceramics department. Ceramics is such a material-driven process—you start with this formless, muddy material and quite quickly turn it into something with shape. Then you fire it, glaze it, fire it again. It’s a process of transformation, and I think that really shaped how I see materials.

That was my first real experience with making things, and looking back, it was quite formative. Ceramics let you create both sculpture and functional objects, and I always preferred that. In fact, when I was about 14, I was making and selling cannabis pipes to my schoolmates—that was my first business, really. So from the beginning, I was entrepreneurial, and I liked that transactional nature of making. Creating something with a function was more interesting to me than making purely sculptural pieces.

Later on, I got into music and other interests, but it was only when I discovered welding that I found a technique and a material that allowed me to be truly experimental. Metal is very forgiving. If you make a mistake, you can cut it, rebend it, weld it back together—no problem. You can’t really do that with wood or ceramic. There’s a kind of elasticity in steel, a versatility and strength, and then there’s the way you join it—with fire—which I found incredibly fascinating.

So steel became my big revelation. It was the material that really allowed me to transform ideas into functional objects that people wanted to buy. But my relationship with materials keeps evolving. I get obsessed with different ones all the time. My process is usually to dive deep into a material, investigate it as much as possible, and try to reach conclusions that others might not.

More recently, I’ve been fascinated by glass. I’m starting to explore textiles, we’ve been working with cork, and of course, we continue to use wood—and even returned to ceramics again. And in terms of metals, my current obsession is aluminum.

Q: Is there any material you haven’t explored yet that you’re eager to work with?

A: Yeah, I’ve actually been experimenting quite a bit recently. As I mentioned, I’ve been working with cork, and also a little with mycelium. There’s a growing interest in mushrooms as a material—something that can be grown and manipulated in a very different way compared to more traditional materials. A lot of people are exploring that field right now.

So I’ve been running a few experiments myself, particularly with more natural materials. They’re not necessarily new materials, but rather ones that have been around forever and are now being used or processed in new and innovative ways.

Q: Were there any moments, encounters, or reference points in your early years that helped shape your creative approach? Many designers often cite childhood experiences or early influences that continue to resonate in their work.

A: Some people, knowing I was involved in music, ask whether that influenced my design work. But it wasn’t so much the music itself as it was the nature of the music business in England.

In that scene, you learn your own instruments, you write your own songs, you manage your own creative output—and then you turn that into a business by making records or promoting your own concerts. That do-it-yourself attitude really stuck with me, and I carried it into my approach to design. In the beginning, I didn’t feel the need to be an expert or to be part of any formal or conventional infrastructure. I felt free to create on my own terms, and that sense of independence came directly from my experience in music.

Being part of that scene—the music world, then the club scene—was deeply entrepreneurial. You made your own luck. You earned money by having ideas and pushing them forward yourself. That mindset was a big influence on me early on.

Another key moment was when I started working for Habitat, which was a big homeware company then owned by IKEA. That’s when I really entered the more conventional world of furniture and design. I got to travel around the world, visiting India, Poland, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Italy. That exposed me to the world of big businesses: retail, branding, marketing, catalogues—all of it.

Meeting Giulio Cappellini and working with an Italian company was also hugely influential. Italian companies truly believed in design in a way that British companies didn’t at the time. That passion for design, and the way it was embraced in Italy, was incredibly inspiring for me.

Q: The S-Chair you designed in 1991 for Cappellini remains one of your most iconic creations. Looking back at that project today, how do you see its relationship with your current work?

A: Well, I think what’s interesting about that chair is how it’s followed me through all the different stages of my career. I first made it in my studio using found objects—scrap metal, reclaimed rubber from the car industry. Then I remade it using natural materials, and that version had a bit more success. It became my first production chair—the first one I ever produced in quantity.

Later, with Cappellini, it evolved into more of a luxury object and eventually ended up in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. So it’s a piece that has really stayed with me over time.

For me, it also represents the way I’ve always worked: directly with materials, often learning through trial and error. The very first version was actually made for a friend who had a hair salon. It was a rotating chair—quite ugly actually—but I sold it to him, and it stayed in use in his salon for quite a while. Then I made another version, and then another.

That iterative, hands-on process is still how I like to work today as well. I prefer making full-scale prototypes rather than jumping straight into computer design. Whether it’s cardboard, wire, or something else, I want to see the object at full size as soon as possible to understand how it inhabits space.

In fact, I often have to pull the designers away from their screens and push them into the workshop to make real, physical versions. That way, we avoid a lot of mistakes early on.

Q: As you return to Salone del Mobile 2025, what can you tell us about your presence this year, and how do you think the way this event is interpreted and experienced has changed within today’s design landscape?

A: Well, Salone is still absolutely fabulous. It used to be the place where we kept every detail under wraps until the very last moment and then unveiled everything in Milan. But that’s changed a bit—we’re now treating Milan more like a summary of the year’s work rather than saving everything for one big reveal.

There are a few reasons for that. One is timing. We’ve done a lot of outdoor furniture this year, and by the time Salone comes around, it’s already spring—too late in the season for outdoor launches. Everyone’s already bought what they need. So we’ve pre-launched our new aluminium outdoor range, called Groove, in sunnier places like Australia, Morocco, and Thailand. I’ve been traveling around promoting it, and while Milan will be its first European presentation, the collection will already be a few months old by then.

We’ll also be introducing some new lighting products—softer, more functional pieces. One of them is called Pose. We’ve already released some images.

Another one is called Soft, which—as the name suggests—is less metallic and more textile-based, a bit gentler in feel.

Then there are the sofas. We started that project about eight months ago, and while they’ll be new to Milan, again, they’re not completely unseen.

Of course, Milan remains an incredibly important platform, but it’s also become more competitive—with massive brands like Moncler, Mercedes, Google, Hermès. So we’re considering taking a slightly different approach, maybe going big every two years instead of every year—more like what many Italian companies already do.

Q: Your studio has collaborated with a wide range of industries—from hospitality to technology. Are there any unexpected collaborations we can expect in the future?

A: Yes, we’re currently working with an electric car company, which is definitely outside our usual territory. We’re exploring a number of categories that we wouldn’t naturally distribute ourselves. There’s only so much we can realistically do—we already handle furniture, lighting, accessories, even perfume—and there’s a limit to how many product areas we can be true experts in, especially when it comes to developing, manufacturing, and distributing them.

Last year, for example, we completed a major project with the Turkish bathroom company VitrA. That was a great collaboration because it still relates to the home and interior design, but it’s not a product category we would typically handle ourselves. We are in talks with a few other companies at the moment, but nothing I can really talk about just yet.

Q: As you mentioned, today’s world feels increasingly saturated—with fast-changing trends, digital experiences, and constant shifts. How do you ensure your designs remain timeless in this kind of environment?

A: You’re absolutely right—it’s becoming more and more difficult to create things that are both unique and timeless. Fortunately, I’ve had quite a bit of practice, and over time I’ve gotten better at predicting what has the potential to last.

Sometimes I see my own pieces coming back around—in antique shops in Milan or London, for example—sitting alongside 19th-century furniture. It’s fascinating to witness that shift, where your work starts to appear in a vintage or second-hand context, gaining a second life.

I think the key to being timeless is doing something which is original. When you’re creating something truly new—when you’re the first to define a certain typology—it tends to stand the test of time.

A lot of what we do also involves stripping away the unnecessary. We avoid surface decoration and anything purely ornamental. Instead, we focus on the essence of the object, aiming to keep it clear and functional without distractions.

Q: One last question: if you could give one piece of advice to young designers looking to push boundaries, what would it be?

A: Well, I tend to always give the same piece of advice to young designers, and it really comes down to two main things.

First, practice. I think especially in university or college, you often end up doing just a handful of projects per term, which can be quite limiting. But like with music or any other skill, you only get better by doing it constantly. You need to practice every day, work on lots of ideas, and not get too attached to any one of them. High productivity and continuous output are key to becoming a better designer.

The second thing is about retaining your uniqueness. In a world overwhelmed by visual noise and endless external influences, it’s more important than ever to find what sets you apart—what makes you special—and express that in both your work and your communication.

It’s easier in some ways now, because we have so many tools for sharing images and ideas that didn’t exist before. But it’s also harder because so many more people are doing it. So finding your own point of view—your own attitude that people can recognize as uniquely yours—is absolutely essential.